Including sculpture, video, and live plants, this project is based on the role that oak trees, specifically the California blue oak (Quercus douglasii), play in the ecosystem of my childhood (developed for Emergent Ecologies, Spring 2016). Quercus douglasii is endemic to a ring of land around California’s Central Valley. In 1987, my parents (with my sister and me in tow) moved onto five acres of blue oak woodland outside of Placerville, California. Designing and building a house to live in involved siting it in and among a stand of mature blue oaks. One of these large trees ended up just a few feet from the back door of the house. Due to the slope of the land, its massive branches were at eye level when we sat at the dining room table and it formed the backdrop for many family interactions. When I was 10, we tied a rope swing from its branches. I fell off the swing and broke my wrist. As an angsty teenage artist, I made multiple paintings of the tree in a slightly psychedelic, pointillist style.

After I left for college, the tree began to fail. Perhaps it had suffered root damage from the foundation of the house, or maybe the new landscaping job didn’t agree with it. Over several years it dropped the majority of its leaves and its bark began to peel away in sections, revealing smooth hardwood beneath. As it faded to silver, the woodpeckers moved in. Acorn woodpeckers (Melanerpes formicivorus) use standing dead wood (snags) as granaries. They drill perfectly sized holes, then pack each one with a single ripe acorn. They often live in large family groups (breeding collectives), and all are involved in stocking and protecting the granary and rearing the young. The group that colonized this snag consisted of around six individuals.

The woodpecker family used the decaying snag as home base for more than ten years, and we all enjoyed watching their intricate process of sculpting it into the ideal habitat. They drilled countless acorn-sized holes into its surface, carved out several larger nest cavities, and defended it with loud, raucous calls.

Later, they began to excavate the plywood walls of my parents’ house, shoving acorns into any crack they could find and adding their signature holes where the wood was deep enough. This activity, combined with the fact that the tree was beginning to rot quite significantly around the base, lead my parents to reconsider their choice to leave a standing snag just feet from the house. In the spring of 2014, I got a call from them telling me they were in the process of making a difficult decision: they had consulted with an arborist and were thinking about taking down the remains of the tree. They were concerned that if they didn’t do it right away, the birds would lay their next brood of eggs, and they’d need to wait another year. All the memories attached to the tree washed over me in that conversation, and I decided to make a trip home to document its dismantling. Over a period of three days I spent as much time as possible watching and filming the tree and its many inhabitants, and when the arborist and his team arrived to take it down, I documented that too. At the end of the weekend I went home to Brooklyn with hours of footage and several chunks of acorn-embedded of wood.

For two years the footage sat dormant, then this spring I had another phone conversation with my parents concerning oak trees. The woodpeckers had moved to a snag down the hill maybe fifty yards from the house, but were still calling the area home. Fall 2015 was a mast year, and perhaps reveling in the abundance of acorns, they had crammed the gutters on the house to the brim with acorns. And now those acorns were sprouting into little trees. My folks found it sad to clean them out and compost them, but we all chuckled a bit at the turn of events.

At some point during the conversation my mother joked that maybe these unwanted (weedy) little oaks should just come live with me in Brooklyn. Although initiated in jest, the idea quickly became reality. A few weeks later I received a priority mail package full of blue oak seedlings gleaned from the gutters.

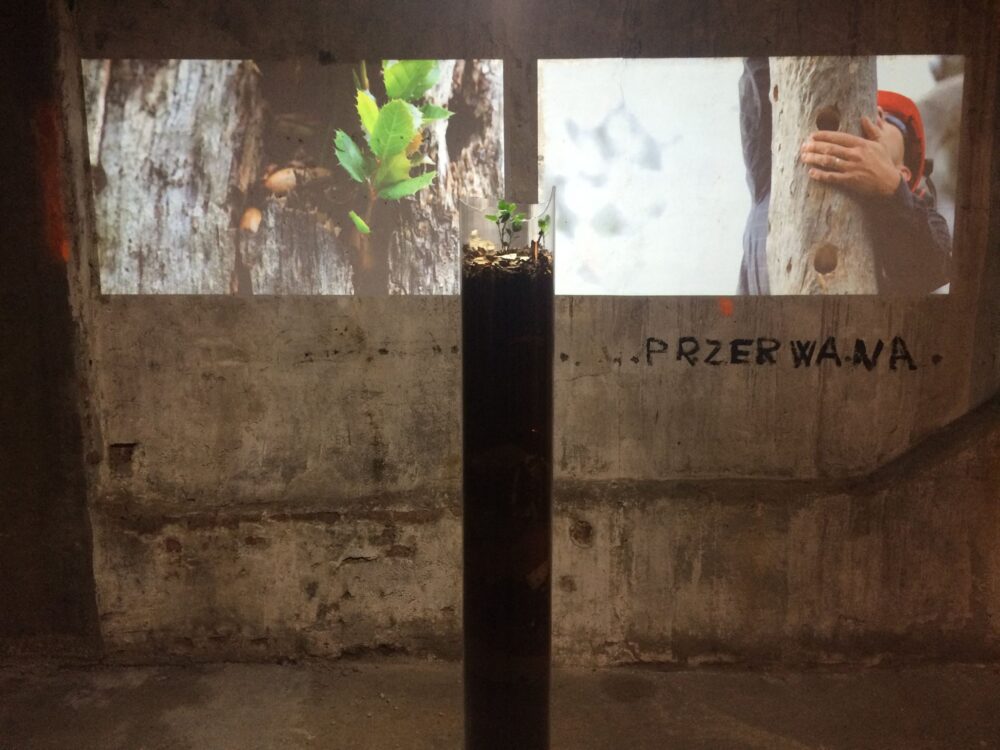

Soon after I finally cracked open that footage from 2014 and investigated it. Initially it was a bit hard to watch, but it’s now edited into a thirteen minute meditation on oaks, acorns, chain saws and human-nonhuman interactions.

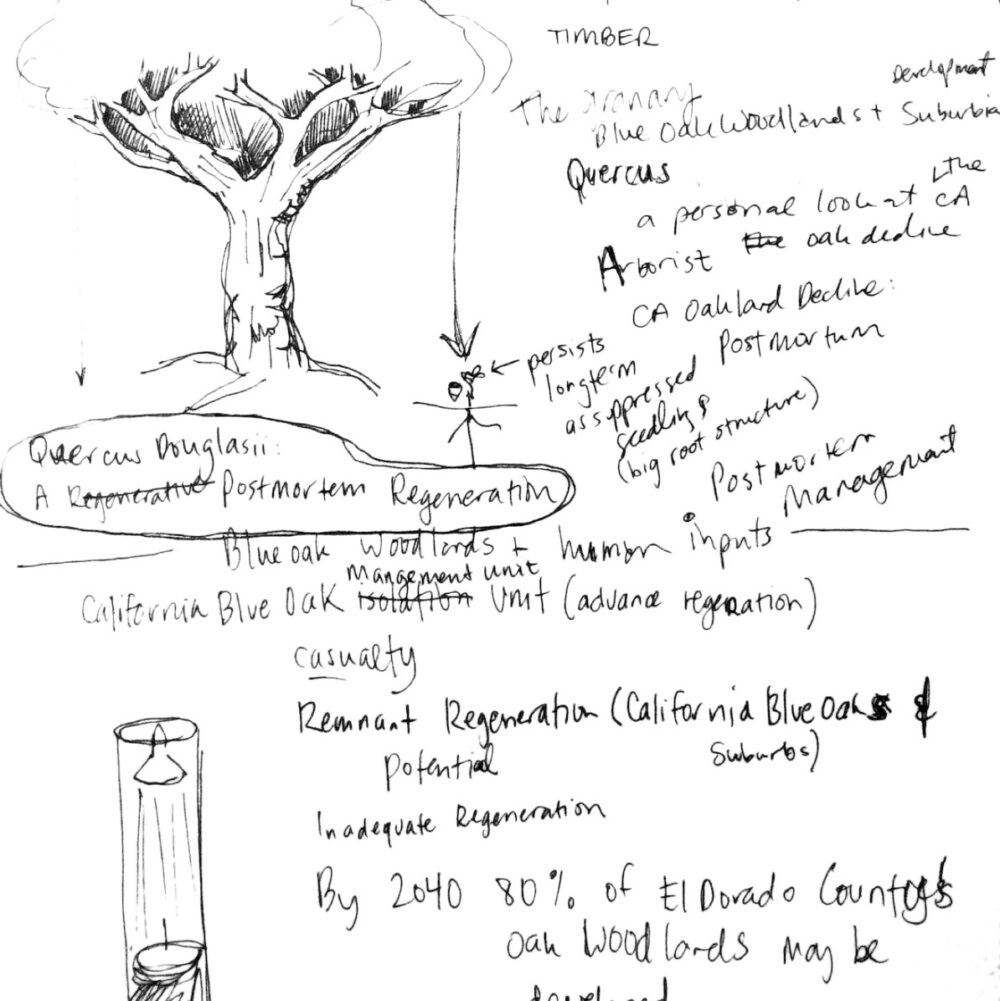

I’ve also started investigating a fascinating web of ecological, social and conservation issues that are tangled up in this iconic tree. “Advance Regeneration” is a reference to the fact that blue oak seedlings often sit for years beneath their parent tree, growing a robust root system but staying just a few inches high above ground, waiting for a gap in the forest canopy that will allow them to go through a spurt of growth and into adulthood. This period of waiting is referred to as “advance regeneration”: it provides a stock of young trees well-prepared to regenerate and replace the generation that came before. Changing climate and human land use patterns have made this stage of an oak’s life (the spurt of growth between seedling and adult) more perilous, and there is evidence that in certain areas blue oaks are failing to regenerate fast enough to replace those that are dying off. There are a plethora of reasons for this, but grazing, competition from dense annual grasses introduced from Europe and hot, infrequent forest fires probably play a role.

My young oak saplings, living in my studio beneath artificial light, have no parent tree to contend with, and little chance of finding their way to adulthood. I’ve saved them from certain death in a municipal compost heap, and consigned them to the purgatory of art object. One particular vigorous clump of seedlings now lives at the top of a column of plexiglass filled with layers of soil, some rich oak leaf duff of California origin, some sourced from construction sites in Brooklyn. This six foot high anthropogenic mixture represents the six feet a young seedling needs to obtain post-advance regeneration stage to have a good likely hood of reaching adulthood.