Started in 2012, Feral Hues and Invasive Pigments is a public fieldwork, writing, and studio-based project that revolves around making watercolor paint from the leaves, petals, and berries of the spontaneous plant beings (aka weeds) who thrive in areas heavily impacted by urbanization, industrialization, and climate change. My zine-style paint-making guide is here, and I also have a more recent short book on the topic: Feral Hues.

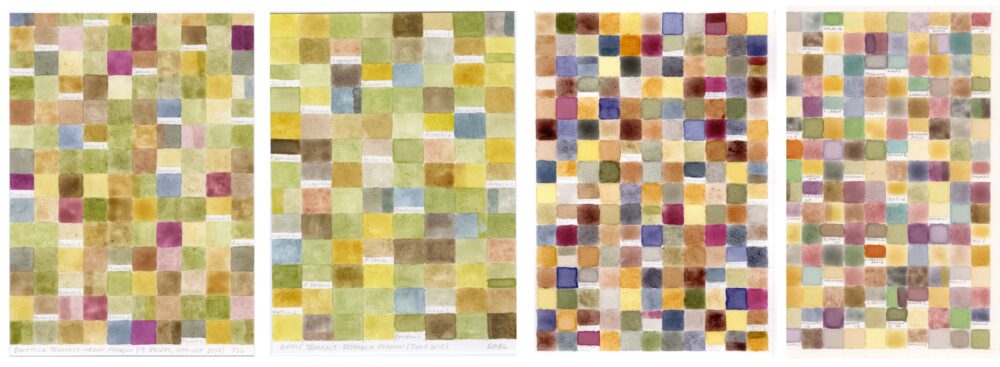

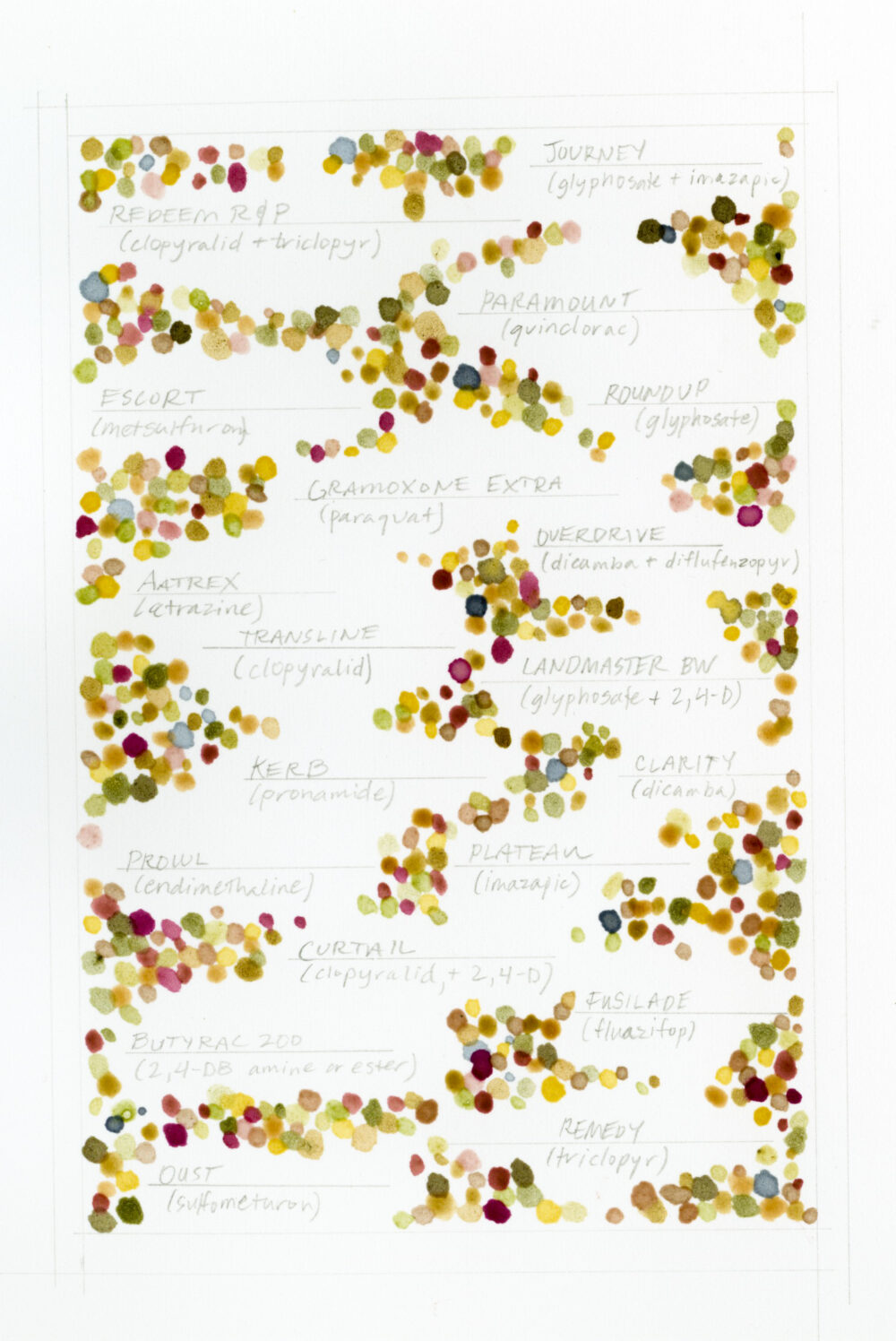

From the brilliant blue of Asiatic dayflower, thriving on copper mine tailings in southeastern China and in monoculture crop fields in the Midwestern US, to the deep magenta of pokeweed, sprouting from deteriorating parking lots in Taipei and concrete riverbanks in Los Angeles, weedy plants are cosmopolitan and resilient. Across shaerd habitats, I work with local participants (humans and plants!) to document the palettes offered by the vegetal beings who build our shared habitats. Through group harvesting sessions, paint-making, art-creation workshops, gardening experiments, and solo studio and research work, I develop palettes that directly reflect the land that grew them, and use those palettes to inspire maps, charts, guides, videos and texts that explore plant-human relationships in the face of climate chaos. Making these palettes provides a hybrid, hands-on approach to contending with ecosystems impacted by extraction that is both flexible across habitats and intensely site-specific. Engagement with the vegetal beings who are learning to heal land damaged by extraction is both nourishing and sobering.

The drawings and maps depicted here detail species’ points of origin and spread through contact with humans, while the pigment diagrams demonstrate connections, both metaphoric and physical, between plants, pigments and urban habitats. The workshops and walks focus on ameliorating plant awareness disparity, cultivating cross-species solidarity, human and plant adaptation to life in cities, and of course the multisensorial delights of making and using paint.

Through the gathering, cultivating and processing weedy and feral species on an intimate scale, the project encourages dialogue around the wider implications of labeling certain life forms as “alien”, “exotic” or “invasive” (and thus dispensable/disposable) and develops plant-human connections in habitats where people are often alienated from the vibrancy and central importance of plant life, from sidewalk cracks and strip malls to so-called “vacant” lots and superfund sites. Current updates about the project are accumulating at #invasivepigments, archived blog posts from the project’s early days are here, and additional context for the project can be found on my writing & press page. Also available is my recent zoom lecture, “Feral and Invasive Pigments: Learning with and From Weeds through Ecosocial Art,” part of Eclipta Herbal & Krater’s Invasive Species Proposal Series.

The video below documents the process of creating watercolor paints, from plant collection to processing to painting:

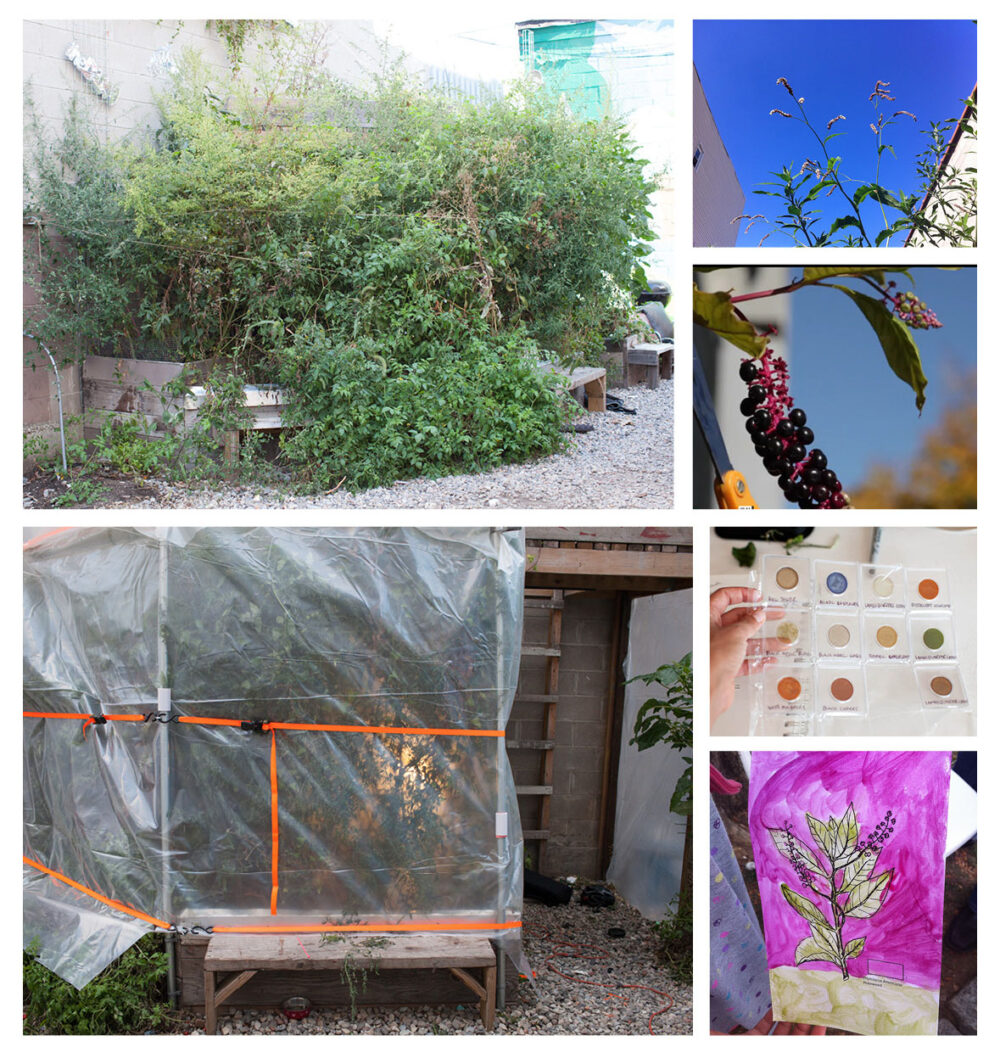

Feral and Invasive Pigments was on view at the Center for Strategic Art and Agriculture from November 7th 2014 – January 15th 2015. The CSAA also hosted the first Invasive Pigments Garden, documented below as it evolved from bare earth in March of 2014 to a towering canopy in the fall. There is a video about that process here: Spring to Senescence.

(thanks to Flickr users clspeace, treegrow, esagor, Esteve.Conaway and klm185 who provided Creative Commons licensed photos for this piece!)

Black cherry (Prunus serotina) is native to the eastern United States and South Eastern Canada. It also lives in Europe, where it is considered invasive in several northern and central European countries. It was among the first to American trees to be introduced as an ornamental in European gardens (arriving in England as early as 1629) and has successfully naturalized in a range of temperate climates.

Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) is native to Eurasia. Since Europeans arrived in the northeastern Americas, it has spread throughout much of the northeast and mid-west United States and Canada. Young shoots were eaten by peasants in Europe, so its introduction may have been purposeful. It thrives in forested communities and edge habitats. With no known natural enemies here (deer avoid it), it has the potential to spread broadly, specifically into areas disturbed by human activity.

NEWS AND PRESS

- Painting with Invasive Pigments, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, Front Matter Blog, January 2018

- Seeing the Art Through the Weeds, SciArt in America

- A Panel on Cities and ‘Weediness’ Silent Barn in Bushwick, Edible Brooklyn

- Ellie Irons and the Art of Survival in Invasive Pigments, Cool Hunting

- Making Paint the Natural Way, AIGA Eye on Design Blog

- Invasion Ecology: Ellie Irons’ Urban Pigment Garden, Artvironmentalist

- Interview, And Freedom For

- How Soon is Now? A Precarious Environment Roots in Art, Hyperallergic

- Painting with the City’s Invasive Plants, Hyperallergic

- Using Nature to Depict Itself, The New York Times

REFERENCES

Many of the facts stated above are drawn from Peter Del Tredici’s book Wild Urban Plants of the Northeast: A Field Guide. Other useful resources for information on weedy, introduced, naturalized, and invasive plants include:

*The common name pokeweed is most likely a contraction of various Algonquin language terms for plants producing red dyes and the common English term weed. In Powhatan, an Algonquin language that was spoken in current-day Virginia, the term pocoon was used to refer to several dye producing plants, and has made its way into the current common name for the “wildflower” Lithospermum canescens, also known as hoary puccoon, whose roots yield a red dye (Benda, n.d.). Among the Lenape, who speak the Algonquin language Unami, the term for red dye is pèkòn (Lenape Talking Dictionary n.d.). As the Lenape Talking Dictionary notes, “Around the year 1600 the Lenape language was spoken by thousands of people. Now, the remaining speakers who grew up with Lenape as their first language have all left this life. We can be grateful that some of our elders took the time to try to preserve the Lenape language for us. They did this by teaching classes, making recordings, working with younger tribal members and with linguists” (Lenape Talking Dictionary n.d.). This is something I think about every time I visit with poke.